To date, much of the academic research on Bitcoin has lacked high-quality data and rigorous review. It’s time to fix that.

This is an opinion editorial by Rupert Matthews, a lecturer at the Nottingham Business School.

Even though the Bitcoin network is open source and accessible to anyone with an internet connection, the Bitcoin community can at times be viewed as closed to new ideas, with many stories of people excluded as a result of promoting and supporting “non-Bitcoin activities.”

At the same time, the benefits of Bitcoin are immediately apparent to those within the community, who also need to support the sharing of information on Bitcoin to “no-coiners” in order to support wider adoption. Unfortunately, broader perceptions of Bitcoin in the media and the “old guard of Wall Street” have meant that the education process can be an uphill battle that must first dispel mistruths before actual education can begin.

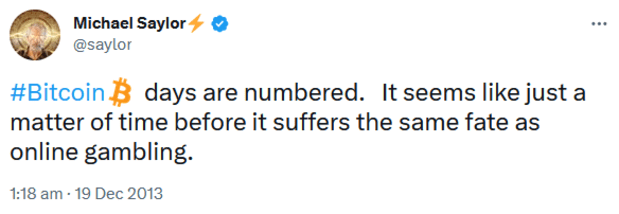

Please remember, even one of our most ardent supporters was once a no-coiner too:

It is also worth remembering, no-coiners cannot all be Michael Saylors, and are not all lucky enough to have close personal friends (thanks Eric Weiss) willing to take the time to clearly explain the concept to us, or the personal motivation to spend thousands of hours educating ourselves. We likely needed several touch points, combined with some base understanding to create the mental curiosity to ask: What is money? And where does money come from?

Saifedean Ammous’ works are some of the best, most widely-referenced sources for answering these questions, but people still need to be willing to read the 274 pages of “The Bitcoin Standard” to access them.

The problem is then, not only whether we have the voices to promote education, but also whether we have enough voices to both compete against those selling their “assets of choice” from Wall Street, but also against uninformed journalists (who are often unable to own the assets they report on), and are greater in number or have wider audiences.

Unfortunately, the sources of conflicted views of Bitcoin don’t end with Wall Street speculators and journalists. Nic Carter, in his critical review of the recent White House report on the environmental impact of cryptocurrencies, highlighted the risks associated with “academic sources” that have a veneer of credibility but are ultimately uninformed. As a result, while something like the “White House Office Of Science And Technology Policy” (OSTP) would suggest the utmost academic and scientific rigor, as Carter put it, “That is where you’d be wrong.”

Questioning ‘Academic Rigor’

This gap in verifiable academic voices led me to begin my own academic journey into Bitcoin by not only consuming material but also using my experience to venture into carrying out research and writing about Bitcoin from my own perspective.

A cursory glance of the works highlighted by Carter provided some easy wins for understanding how pseudo academics are able to publish works under the guise of academia (specifically, the works of Alex de Vries). More disturbingly was, within further research, finding actual academic sources that were both peer reviewed and published within reputable journals drawing from these sources and allowing them to significantly affect their findings. The influence can also be seen within the references that make the most fanciful predictions (such as this one by John Truby), catastrophizing the impact of Bitcoin mining on the environment, that too are published within academic journals, that themselves draw from the sources identified by Carter.

This creates a situation where, while the original sources may be non-peer reviewed, commentary pieces or personal blogs, their views can directly impact findings and models that are presented within more highly-regarded, peer-reviewed scientific journals (see this example).

This places an uncomfortable lens up to the academic process of peer review, where those reviewing academic research on Bitcoin appear to not be knowledgeable about Bitcoin. More concerning for academia more generally, is that this also suggests that the academics reviewing research on Bitcoin are not questioning or checking the sources that are being drawn from. If they did the most cursory job of checking the credibility of a citation of a website or even acknowledge that a particular piece of work was actually a non-peer-reviewed “commentary,” clarification would be required by the authors before such works were accepted for publication.

Further concerns are raised when considering time-pressured academics who read such “peer reviewed” sources. They could, themselves, develop views that are influenced by the work, without realizing the quality/bias of the sources that are being built on, and potentially pursue anti-Bitcoin research agendas.

Bitcoin is becoming renown for being cross disciplinary, with those studying the topic becoming knowable on a range of fields, from Austrian economics to the environment, from personal time preference to food supply chains. Unfortunately, academic journals are widely acknowledged to focus on quite tightly-defined domains they accept research on. This means that, unfortunately, accepted, topic-specific models of research and analysis may not be able to capture the complex nature of Bitcoin research.

To illustrate this, a highly-cited economic article from 2015, that follows the accepted approaches of rigor, published within a high-quality journal, found that the “long-term fundamental value (of bitcoin) is not statistically different from zero.” Given that Bitcoin started 2015 at around $318 and ended the year at $430 and has risen dramatically since this time, one can only imagine the potential “saltiness” of the academics who presented these findings and how this may have affected their long-term view of and research journey in Bitcoin.

How Academics Can Improve On Bitcoin Research

While the idea of establishing new research journals focused upon Bitcoin are a worthy way forward, academic journals take time to develop reputations and academics within fields tend not to stray far from the sources they are comfortable with. Academics are also incentivized to publish within established journals by linking research outputs to career progression, meaning a new journal may not be an avenue for development in the short term.

I am a great fan of the Bitcoin Policy Institute, which does invaluable work promoting research and advocacy to improve understanding on Bitcoin, but it can only have so many members with its current level of funding (without considering the issues associated with greatly-increasing membership). This means that increasing the membership of such institutions may also not be the best avenue for development.

To reflect on these potential issues, my three suggestions for those working in academia are: Firstly, to identify ways of conducting academic and rigorous research from the perspective of their area of knowledge to be published within journals related to their own discipline. Secondly, allocate resources specifically for responding to published research that is inaccurate, incomplete and biased, through communication with the editorial boards of the respective journal. Thirdly, include Bitcoin within the topics they are willing to review papers on, thus helping prevent articles that inaccurately present views of Bitcoin from being published. Through this process, as more academics enter the field, they will be able to benefit from robust academic debates, with high standards they can aspire to, hopefully allowing themselves to write work that contributes to the scientific understanding of Bitcoin.

These suggestions are unlikely to solve the bias presented by journalists or politicians, but I believe they represent a way to improve the academic foundations of Bitcoin understanding. Academics pursue research with the aim of unearthing new knowledge and understanding, on the journey to establishing new or refining existing truths, that build upon the scientific methods that underpins the modern world. Unless this foundation is established, and people aiming for quick academic wins are prevented from publishing their work, journalists and politicians will continue finding sources that are aligned with their views on catastrophizing the impact of Bitcoin. If journalists and politicians are unable to draw from low grade “research” that does not stand the test of critical review, they will not be able to distribute these views to the general public. While this may not solve the problem, it might just be able to move the debate in the right direction, and allow academics to be the critical voices that are underpinned by scientific rigor. If the general public’s view of Bitcoin is not misinformed, there is one less barrier to overcome in the process of orange pilling a future Bitcoiner.

Members of academia are at times regarded as conducting their research from ivory towers that have only limited impact on practice or the lives of everyday people, but the OSTP’s recent report and wider academic literature shows that the increasing interest in Bitcoin is magnifying the impact of Bitcoin-related research. Unless action is taken to ensure the high standards of academia are maintained within research related to Bitcoin, not only will the progress of Bitcoin be slowed, but the reputation and standing of academic research more widely will be damaged.

This leaves me in a position where I would like to provide a message to academics who use low quality or biased data within their work and reviewers who do not check the sources that are being drawn from. As an academic myself, my message is: Shame on you. As a Bitcoiner, my message cannot be published, but believe me, it is from the heart and does not pull punches.

This is a guest post by Rupert Matthews. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.